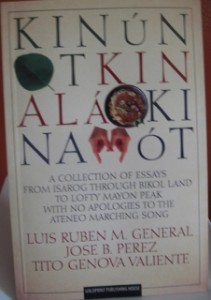

Kinunot, Kinalas, Kinamot, penned by Luis Ruben M. General, Jose B. Perez and Tito Genova Valiente, appears to have the trappings of a partisan’s shrillness. The subtitle, “Essays From Isarog Through Bikol Land, To Lofty Mayon Peak,” smacks of Ateneo bias by the writers since the line was taken from the first two lines of the Ateneo de Naga school song. But as one flips through the pages of the book, one discovers that the authors, Ateneo de Naga High School batchmates, Class ‘72, have collectively internalized, if not lived, the sense of pride that comes with the song, “which is about destiny and geography and determination,” as Valiente writes in the preface.

Kinunot, Kinalas, Kinamot, penned by Luis Ruben M. General, Jose B. Perez and Tito Genova Valiente, appears to have the trappings of a partisan’s shrillness. The subtitle, “Essays From Isarog Through Bikol Land, To Lofty Mayon Peak,” smacks of Ateneo bias by the writers since the line was taken from the first two lines of the Ateneo de Naga school song. But as one flips through the pages of the book, one discovers that the authors, Ateneo de Naga High School batchmates, Class ‘72, have collectively internalized, if not lived, the sense of pride that comes with the song, “which is about destiny and geography and determination,” as Valiente writes in the preface.

The title can be misleading especially to food enthusiasts. The book is not about kinunot, a Bikolano dish whose ingredients include shark meat cooked with coconut cream and malungay leaves. Neither is it about kinalas, a Bikolano noodle soup cooked in broth of a skinned pig’s head until the meat falls off. And it has nothing to do with kinamot, a manner of eating using one’s hands.

The title can only be read as a means to whet the appetite of readers to the more important dish – the Bikol culture and everything that it represents. The book includes a preface, an introduction and forty short essays that cover diverse issues relevant to students, professionals, religious, and Bikolanos who want to discover the past, understand the present, appreciate the value of relationships and everything that may seem mundane, but in reality is not. In 147 pages, the authors are able to articulate their love for Bikol in a manner that is easy to comprehend.

Simply put, Kinunot, Kinalas, Kinamot is the magnus opus of General, Perez and Valiente who want to share through their writings, deftly and often powerfully, their memories of Naga and the Bikol Region, the people they’ve met in their journey, the places that have made a dent in their lives, the significant human relationships now etched in their hearts that have made them strong individuals and proud Naguenos and Bikolnon.

The authors represent a new wave of Bikolano writers whose writings are simply readable and sprightly. They not only write as they feel and see, but they write with a mission.

General writes by giving the readers a glimpse of the past, enlightening the readers in many facets of local history never before discussed in formal settings. He consistently shows some astonishing revelations about Naga whether he writes about the old street names in Naga or when he questions the rationale behind the local Church’s attempt to make the traslacion a “penitential in character” or when he remembers the carretelas in his youth. He laments the emerging proclivity among Bikolanos to speak in Tagalog rather than in Bikol.

Perez, true to his journalistic calling, writes about things that matter to the daily lives of ordinary Bikolanos. Although a few of his essays are utterly tame, that is, not as political or controversial, as General rebutting a local politician for wanting to divide the province of Camarines Sur, he allows his readers to draw parallels or lessons from his experiences, as he writes about successes in his family or raising funds for a classmate suffering from cancer. He approaches his subjects with tenacity just like when he critiques the political dynasties in Bikol and with light-heartedness as he lauds a friend for being appointed by Pnoy in government. But make no mistake about it, Perez is a crusader. He opted for a jail term rather than compromised his principle over an article he wrote on alleged dirty money that changed hands over a case against City Hall.

Although Valiente’s medium is prose and his language rich, as pointed out by Doods Santos, literary critic and Bikolista in her introduction, his style does not seem to affect his message. He can still powerfully, though with a tinge of sorrow, express the same appreciation and admiration when he pays tribute to Socorro Federis-Tate, his friend Rudy Alano and his cousin Jessie Badillo-Snyder. What better way to celebrate their lives than write about them, Valiente seems to be saying. The point is whether he is writing about people or about places like Ticao Island or Sorsogon or about the Japanese quilts, his insights are grounded on what essentially matters in life. His humanness blends well with his style creating a strong rapport with someone who may from time to time dwell with one’s emotions.

What strikes me the most about the book is the dedication: In the end, we offer this book to Fr. James O’Brien, S.J., who founded the Ateneo de Naga High School Bikol magazine, “An Maogmang Lugar.” From Fr. O’B the New Yorker, we learned to once more love the Bikol language (a language, he would insist, and not a dialect of any superior language).

Why dedicate the book to Fr. O’Brien? My guess is just as good as anybody’s.

I like to believe, rightly or wrongly, that O’B, as he was fondly called by his students, succeeded in instilling in the young minds of General, Perez and Valiente that love for Bikol the good mentor religiously drilled into the minds of his students. Naga is lucky to have General, Perez and Valiente answer O’B’s call. And I am guessing this book is the writers’ way of acknowledging – and thanking – O’B’s contribution in making the Bikolanos appreciate and love their own culture.

O’B must be pleased with how his own great meme has evolved through General, Perez and Valiente’s writings.

Thanks to book reviewer and columnist Greg Castilla. I stumbled upon this article very early and, I assume, first review of our book.

We had fun writing the essays, producing the book, and launching it. Whatever gravitas is felt in some of our essays, it must be one of life’s pleasant surprises. Cheers.