Special essay by Tom Mcphail

Thus, Marcos was unable to personally identify with the kind of god-kings or sultans of a glorious past for political gain (regardless of how much he may have wanted to). In Marcos’ own words, there was “no Taj Mahal, no Angkor Wat, no great wall that stands with us to remind the colonial intruder of his insolence in affecting to ‘civilize us’ in exchange for exploitation”[1]. What we’re seeing is a kind of contradiction playing out for Ferdinand Marcos between identifying with tradition but being limited to preexisting cultural discourses such as the “damaged culture” dialogue and contemporary modernity and development on an international scale (both cultural and economic) [2]. This process, described by George Kubler and Indigenismo, is a uniquely post-colonial twentieth century phenomenon .

“One Simply cannot be a nation-state, an ethnicity, or a race without a proper and corresponding art, with its own distinctive history or trajectory which ‘reflects or models the broader historical evolution of that identity…” – Donald Preziosi

Dialogue between the old and new can be seen to play out in the implementation of a cultural and architectural agenda of the first lady, Imelda Marcos. Mrs Marcos’s involvement in the propagation of a process of ‘cultural rejuvenation’ was not simply symbolic, and her relevance is on going.This essay posits that Imelda’s influence remains significant to this day, as we will see her on going support of the art and of cultural institutions. Her conspicuous participation in affairs of the state made her the second most powerful and visible political figure in the nation, and the dramatic and modern architecture is to many, symptomatic of an edifice complex .

It is Imelda who is chiefly responsible for the official architecture and art under the regime, attempting to manipulate it for the reincarnation of a vernacular civilization fashioned from a synthesis of indigenous and cosmopolitan aspirations of modernity [7]. Imelda herself wrote two monograph’s on architectural imagery to signify the modernizing thrust of the regime, Architecture: The Social Art (1970) and Architecture for the common man (1975) [8]. ‘The True the Good and the Beautiful’ became something of a kind of a catch phrase for Imelda’s agenda, but it perhaps the most clear description of the inherent contradictions within her scheme. It was to be used here to describe an aesthetic maxim to be taken by Artists and architects for the establishment of a national myth, however it is undeniably linked with western philosophy [9]. The classic greek philosopher plato’s work on ‘the transcendentals’ forms a primary mode of modern, western thought. Imelda’s own appreciation for the arts wasn’t limited to Filipino artists, spending fortunes on European and American modern artists, and being famously involved in the theft of work by the French impressionist Claude Monet .

The Cultural Centre of the Philippines (CCP) is really the first major building project by Imelda Marcos, and arguably demonstrates how seriously the Marcos regime took the nexus of architecture and society in promoting the aesthetics of power in the built form [11]. Her aims were to promote traditional culture through the construction of museums devoted to folkloric culture, which begun with the Cultural Centre. The centre exists to this day as a primary institution in the Philippines art world and a node in the regional art market, a point that cannot be stressed enough. The CCP cultural convention facility was built on land reclaimed from the historic manila bay, with grandiose plans (that would never come to fruition) to reclaim total 10 kilometers .

The building was an enormous concrete construction, employing cantilevered engineering to create a powerful, dominant and monolithic presence. It is clear from the image below that it dominates Manila bay with it’s brutalist architecture. Brutalism is a style of architecture that flourished from the 1950s to 1970s, spawning from modernist architecture and linked chiefly with governmental building.

Critics of the style suggested that it portrays a cold, ‘totalitarian’ style, though this is not necessarily true. An example closer to home, The University of Technology Sydney tower could not be said present a totalitarian symbol (though it has been voted Sydney’s ugliest building for many years in a row). To Imelda it served its purpose, conveying state power, modern progress, national identity, and the aesthetics of development. It presented to the Philippines what they developed future might look like.

According to Gerard Lico, “in the minds of the Marcoses, a building was not merely a walled structure but a metaphor for a Filipino Ideology, and he process of construction was synonymous to the building of a nation”[14]. Further development projects for which Imelda is chiefly responsible include, the coconut palace, The Batasang Pambansa (malay roofed), The Philippine Village Hotel, The “City of Man” project, the national arts centre, The National High School for the arts, The Metropolitan theater or the Manila Film Centre.

Naturally, such large development projects do not go unnoticed. We might now consider two artists that have responded to such developments, the late Roberto Chabet, godfather of Philippines conceptual art and Oscar Villamiel, a Philippines representative at the 2013 Singapore Biennial and founding director of Manila’s MO Space.

Roberto Chabet passed away earlier this year, his legacy is considered amongst the greatest Filipino artists, he has ongoing relevance to a discussion of what constitutes art in the Philippines[1]. He is also a figure that has gained directly from the cultural centre as an institution, as he was it’s founding director. He also established the 13 award, intended to identify artists who took the “chance and risk to restructure, restrengthen, and renew art making and art thinking…..

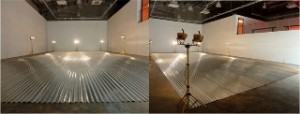

The award was later adopted as a biennial award by Chabet’s successor, the late Raymundo Albano. The Thirteen award is the oldest award program conferred by the CCP, two years ahead of the National Artist Award which started in 1972[3]. Onethingafteranother (2011), pictured above, was presented as part of an large 50 year retrospective of Chabet’s work in 2011, however the initial concept had been developed far earlier but never come to be[4]. Chabet is said to draw heavily on a background as an architect, often focusing on the transitory nature of the common place object.

This work has taken these industrial materials, materials that Imelda’s building efforts had tried to remove or ignore as they did not fit in with an overall aesthetic of development (at times forcefully), and laid them out in a monumental and monolithic structure. Imelda would likely have been quite fond of this grand statement as in a way Chabet is laying out the products of the past.

He doesn’t appear to be for against this process, but recognizes it, and establishes the corrugated iron as symbolic of that move towards national development. Chabet’s installation places itself into a grander narrative of technological development and modernity for the Philippines.

Leave a Reply